Managing spring calving cows at grass is a balancing act between optimising grass utilisation, setting up for the second round, and ensuring milk solids and fertility - all while keeping cost of production in line with targets.

With many herds grazing by day and others looking to get out as soon as conditions allow, it is worth considering the needs of the herd during this crucial early lactation period, says Kevin Doyle, technical manager at Phileo by Lesaffre UK & Ireland.

Managing risk

“The three weeks before and after calving, often called the transition period, have been repeatedly proven to be the most critical time in the cow’s production cycle, followed by the first 100 days of lactation,” says Kevin.

Cows always prioritise milk production over their own needs and if energy supplies drop, they will mobilise body fat to make up for energy deficits. While this is a natural response and required, excess fat mobilisation has serious knock-on effects including impaired fertility, increased risk of ketosis, mastitis and metritis.

A successful transition into lactation is most heavily influenced by body condition score, followed by energy balance, immunity and calcium status.

He says: “Cows experience a major change in diet when going from dry to milking, and indoor to grazing. At this time, nutrient demands are at their greatest and feed intakes are still catching up, which leads to a period of negative energy balance and, in turn, necessary weight loss. However when cows lose more than 0.5 BCS in the first 30 days, this has a significant effect on health and fertility.

“Approximately 75% of disease occurs in the two months post-calving and often stems from the transition period, representing a serious risk to your business.”

Kevin continues: “It is estimated only about 2 per cent of cows in Ireland suffer clinical signs of negative energy balance or ketosis. However, this is only the tip of the iceberg as 30 per cent of cows are thought to be affected by what is known as sub-clinical ketosis which silently impacts herd performance.

“Raised blood ketone levels indicate subclinical ketosis with over- and underconditioned cows at greatest risk.

Subclinical ketosis can mean cows are:

- 2x more likely to be culled in the first 60 days

- 8x higher risk of displaced abomasum

- 5x higher risk of retained placenta

- 3x higher risk of metritis

- 6x higher risk of cystic ovaries

- 22 days longer to first oestrus

“On top of these challenges, we want cows to peak at around 60 days in milk, a benchmark which drives milk volume and solids yield throughout lactation. Reaching this goal can also improve production from grazed grass later in the season and with the peak breeding season occurring at the same time, this is a double risk period.”

Increasing the supply of nutrients that supply glucose needs to be absolute priority as there is an abundance of fat to be mobilised. In most instances, propionic acid is the key nutrient source required to increase as it supplies the cow with around 50 per cent of its glucose requirements. Increasing propionate supply is achieved by offering highly digestible feeds in the form of starch sources, i.e. cereals and highly digestible leafy grass.

Kevin says: “Unless the farm is set up for exceptional quality grass, maize or wholecrop silage, grazed grass is likely to be the highest quality forage available on-farm at this time of year.”

Make changes slowly

At turnout, the move from the winter diet to lush spring grass also represents a significant transition for the microbes in the rumen.

Kevin says: “It takes rumen microbes around three weeks to fully adapt to such a change, so this transition must be gradual to avoid digestive upsets and a subsequent loss of performance.

“The microbial populations in the rumen are used to a winter diet and contain the right balance of species to digest those feeds. When cows begin eating grass, there is a major shift in nutrient profile to which the microbes need to adapt. This is particularly important for the spring calving cow in the vulnerable early lactation period.

“Time on grass should be increased gradually. As a rule of thumb, start with two to three hours of grazing per day, which typically allows intakes of around 5kg DM.”

Balancing the diet

Complementary compounds should balance, not replace, grazed grass in the diet.

“What we are looking for is slower degrading sources of energy. This could include starch primarily from cereals or sources of highly digestible fibre, such as sugar beet pulp or soya hulls, and bypass protein sources to complement rapidly available protein in grass. The higher the quality of the supplement, the lower the substitution rate,” says Kevin.

“Feed should also be fortified with the correct levels of vitamins and minerals to account for deficiencies at grass, particularly magnesium.”

Feeding for cow type and system

Feeding levels should be tailored to the type of cow you are running and ensuring dry matter intakes are not ever compromised, Kevin says.

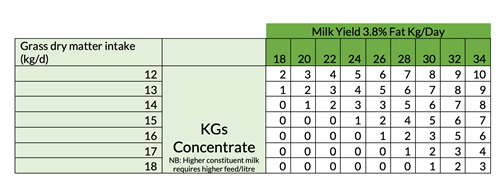

“In theory, for a 600kg cow producing 26kg of milk at 3.8% fat, consuming 15kg grass dry matter per day would require an allowance of 2.5kg of concentrates to meet 100% of UFL requirements.

“On the other hand, a 600kg cow producing 34kg of milk at 3.8% fat would require 6.7kg of the same concentrate, where grass intake is 15.0kg of dry matter.”

It is highly unlikely cows will consume 15kg DMI every day in the first one or two months. It is much safer to assume an intake of 12kg DMI, therefore it is important to account for this when rationing.

“Where grass DMI is restricted, higher concentrate allowances will be required to provide 100 per cent of energy requirements and 12kg DMI should be assumed. This is of particular concern during the first six to eight weeks, when wet weather is prolonged, and when cows are fed grass-silage by night and grazed grass by day early in the grazing season,” he says.

Table 1.

Listen to your cows

Lush spring grass which is high in sugar and low in structural fibre is great for supporting milk yield and milk solids. However, it can also disrupt the rumen microbes resulting in impaired rumen function, increased risk of acidosis and/or sub-acute ruminal acidosis (SARA), and reduced digestive efficiency.

Kevin says: “A typical early warning that SARA may be an issue is a sudden drop in butterfat of up to 0.3% over two to three days. Look for other ‘cow signals’ that can confirm poor rumen function as the cause, rather than raised levels of unsaturated fats in grass.”

Signals include:

- Loose, bubbly dung containing undigested fibrous material.

- Where rumen function is good, 60-65% of the herd should be lying down and chewing the cud by midday, with the remainder either grazing or drinking.

- Low rumen fill scores indicate insufficient DMI, in turn indicating DM availability is low, stocking density is high, or rumen function is poor.

- Butterfat to protein ratio should remain approximately 1.2 to 1.

“By considering the needs of the early lactation cow and how to best complement grazed grass in the diet, we can really help set cows up for a successful lactation,” continues Kevin. “Not only will that help us now, but it can also mean fewer problems later on in the lactation - ensuring the herd reaches the breeding season in good shape and can produce more from grass later in the season.”

Optimising the rumen microbes:

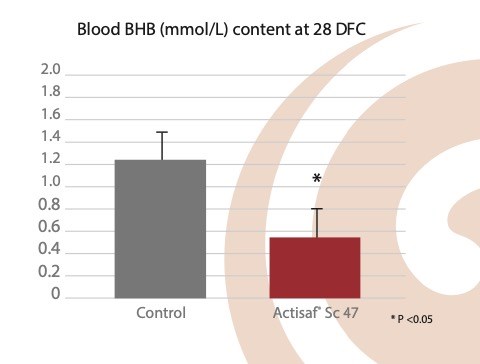

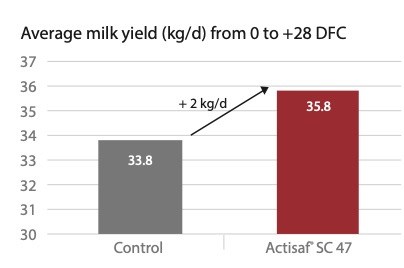

“Specific strains of live yeast like Actisaf® Sc47 maintain rumen function by supporting the microbes responsible for efficient digestion throughout the lactation,” he says.

Actisaf® is proven to ease the transition between diets and helps to reduce the risk of low rumen pH. It does this by stimulating specific microbes that utilise lactic acid and convert it into propionate the main source of glucose for the cow. This in turn raises rumen pH and increases energy supply at the same time.

“Actisaf® is also the only live yeast proven to significantly improve metabolic function in early lactation, leading to reduced blood ketones and improved milk and solids yield.”

Source: L Cattaneo et al., 2023 J Dairy Sci.

To learn more, visit www.yeastsolutions.co.uk or call 061 708 099.